INTERVIEW

Interview with Mr Alexandre Florentin on ’50 degrees Celsius at Paris’

“BY COMMUNICATING THAT MAXMUM TEMPERATURES OF 50℃ COULD OCCUR AT ANY TIME, IT IS POSSIBLE TO CONVEY THE SERIOUSNESS OF THE THREAT.”

DATE: 20JUNE 2025

LOCATION: CLIMATE ACADEMY, PARIS

INTERVIEWER: MIKIKO KAINUMA, TOMOKO ISHIKAWA

The Evolution of the ‘Paris at 50 degrees Celsius’ Mission

Mr. Alexandre Florentin was elected to the Paris City Council in June 2020. In January 2021, he requested the Mayor of Paris to launch the ‘Paris at 50 degrees Celsius’ mission. Between 2021 and 2022, the mission investigated challenges related to crisis management through approximately 40 interviews, and its initial proposals were presented in August 2021. However, conventional reports proved insufficient to capture the attention of the general public.

As a result, in the spring of 2022, a fictional work titled “Paris at 50°C” was released on Twitter (now X). Rather than depicting a distant future, the story portrayed a scenario that could occur as early as the next day, illustrating how everyday life in Paris would be radically affected if temperatures were to reach 50°C.

In July 2022, the Paris City Council unanimously adopted the “Paris at 50°C” mission. Subsequently, from October 2022 over a period of approximately six months, a cross-party group of city councillors conducted hearings and field investigations. This work resulted in the publication of the “Paris at 50°C” report in April 2023 [1]. The report provides a diagnosis of urban vulnerability to the climate crisis and sets out 85 concrete policy proposals.

In October 2023, simulation exercises focused on crisis management were conducted in two districts of Paris, involving residents, municipal officials, and healthcare professionals. Finally, between November and December 2024, the City of Paris successively announced and adopted four major plans: the Urban Planning Framework (the Bioclimatic Local Urban Plan, Plan local d’urbanisme bioclimatique), the Climate Plan (Plan Climat 2024–2030), the Second Paris Environmental Health Plan (Plan Parisien Santé Environnement 2), and the Resilience Strategy (Stratégie de résilience).

Why a Cross-Party Approach and How it Was Made Possible

One of Mr Alexandre Florentin’s key priorities was to address climate change through a cross-party approach. As members of the Paris City Council are subject to regular elections, if a mission were pursued by only a limited group of councillors, there would be a risk of it being discontinued following an election and a change in the council’s political composition.

To secure cross-party support, Mr Florentin deliberately made crisis management the focus of the initiative. Starting with mitigation policies would have inevitably brought divergent political views to the surface, making it difficult to reach a consensus. However, by emphasising the necessity of crisis management in responding to climate change, it became possible to obtain broad, cross-party agreement.

For this reason, the mission initially focused on adaptation policies, providing a shared foundation for cooperation across the political spectrum.

Synergies Between Adaptation and Mitigation

Air conditioning is not a magic solution. Its widespread use can in fact further increase ambient temperatures, but it also becomes useless when systems fail *2 or power outages occur. In response to extreme heat driven by climate change, the City of Paris is seeking to adopt low-tech adaptation measures that are accessible to everyone, consume little energy, and do not rely on high technology.

These low-tech measures include natural ventilation and solar shading in buildings, reflective materials, green roofs and walls, the greening of parks and school grounds combined with permeable paving, rainwater harvesting and manually operated misting systems.

Some of these measures also generate synergies with mitigation. For instance, increasing tree planting as an adaptation measure enhances CO₂ absorption and therefore contributes to mitigation. Other measures—such as building insulation retrofits, white or highly reflective pavements and roofs to improve albedo, rainwater use and permeable surfaces to restore urban water cycles, and mobility reforms including public transport, dedicated bicycle lanes, and converting roads into green spaces—also reduce overall energy consumption.

However, adaptation measures alone cannot improve the climate. For this reason, Paris is now placing greater emphasis on strengthening mitigation efforts as well.

Reform of Primary Schools

Particular emphasis has been placed on reforming primary schools. These efforts are guided by the principle of “building a city that priorities children’s rights and health above all else”. Proposed measures include the thermal insulation and renovation of school buildings, the greening of schoolyards, the creation of ‘cooling oases’, the adjustment of activity schedules during the summer and the introduction of climate education. The Climate Academy has also served as a venue for climate education. Primary schools can be used as local evacuation and refuge facilities during extreme events.

About the Climate Academy

A former city hall building has been repurposed as a publicly accessible space dedicated to climate action. It offers the general public free meeting rooms and workspaces, and hosts training programmes for municipal staff and others on the transition to a decarbonised society. Workshops on topics such as rooftop greening and creating cooler urban spaces have been held, with participation from local residents and children. Schoolchildren also visit the Academy with their teachers to learn about climate change as part of their education.

Importantly, learning at the Climate Academy is not limited to technical or political aspects. Artistic approaches are incorporated too, making the Academy a place where art and action coexist. Exhibitions are held regularly. The Academy operates under the core concept that meeting and talking face-to-face is essential.

The academy’s rooftop has been greened, and explanatory panels on rooftop and exterior wall insulation have also been installed. In addition, a panel depicting an aerial view of a future Paris with widespread rooftop greening—featured in the report “Paris at 50°C”—is displayed, making the site a thoughtfully designed place for learning.

Mr. Florentin spoke about the difficulties of promoting rooftop greening in Paris, while expressing his strong determination to make it a reality. He also pointed out the cultural context behind this challenge: many Parisians feel a deep attachment to the city’s traditional grey and black cityscape, often portrayed in films, as well as to its iconic zinc roofs, and therefore tend to resist changing these features even from the perspective of climate action.

Within the academy, environmental data such as air temperature are also being monitored, making it a place where visitors can learn, based on scientific evidence, which measures are most effective.

Emotional and Practical Dimensions of Climate Adaptation

Living on the top floors of traditional buildings can increase the risk of death during heatwaves, as zinc roofs tend to retain heat. At the same time, however, Parisian rooftops hold strong emotional significance as symbols of the city, so renovation or modification is far from straightforward. Often featured in films, these rooftops embody a deeply rooted image of ‘what Paris is’ for many people.

Discussions surrounding such ‘heritage’ and ‘ what should be passed on to future generations’ tend to be highly emotional, so reaching consensus takes time. The same applies to historic buildings. Many of these structures were designed primarily to cope with cold conditions, i.e. to retain heat in winter, and there is considerable resistance to retrofits involving insulation, ventilation or other adaptations. Some individuals adopt an outright rejection of change, disregarding scientific evidence related to climate change.

For instance, building consensus around the promotion of rooftop greening proved extremely challenging. While the Climate Academy’s rooftop has been successfully greened, many challenges remain before such initiatives can be scaled up across Paris. Mr Florentin aspires to green all rooftops in Paris.

Presenting extreme future scenarios, such as a maximum temperature of 50°C, can effectively convey the severity of climate risks to the public. Meanwhile, policies to reduce car use have gained broad support as they contribute to lower noise levels and improved air quality. Over the past five years, Paris’ urban landscape has changed significantly, with a sharp increase in cycling. However, new challenges have also emerged, including higher cycling speeds and increased safety risks for pedestrians.

Reconsidering everyday habits, such as air conditioning use and energy consumption patterns, is also critical. Advancing a political agenda based on scientific evidence requires considerable courage and perseverance.

Communicating Science to Engage and Mobilize Citizens

Climate action is not something to be pursued for some distant future or for someone else; it is a challenge that must be addressed here and now. Yet for many people, it is difficult to act on events that have not yet occurred.

What is therefore needed is empathy and imagination, achieved through storytelling. Stories could depict a nurse working during a heatwave, a roofer labouring on a scorching rooftop or people working on the streets or in overheated kitchens during extreme heat. Such concrete, everyday stories spark conversations, creating opportunities for people to reflect on climate change in the context of their daily lives. Creating spaces for dialogue, where such conversations can take place and people can connect, is a crucial first step.

For many, the idea of the global temperature rising by 1.5°C, 2°C or even 3°C still feels disconnected from their own lives. However, when the conversation turns to a future in which maximum temperatures reach 50°C, people finally pause and begin to think. While scientists often speak in terms of ‘average temperatures’ and ‘probabilities’, conveying the gravity of this threat requires approaches drawn from the social sciences. Rather than focusing on global averages, it is more effective to help people imagine the impact of extreme maximum values, making the risks more tangible and real.

This is why I started sharing the story of ‘Paris at 50°C’. This is an attempt to encourage people to view climate change as their own problem that demands attention and action, rather than an abstract issue.

Key Points on France’s +4°C Adaptation Scenario and the Challenges of Citizen Participation

Anticipating the severe progression of climate change, the French government has developed an adaptation strategy based on a “+4°C scenario” through PNACC 3, the Third National Climate Change Adaptation Plan *3. This approach is based on the assumption that a global temperature increase of +3°C would correspond to an increase of approximately +4°C in France. While this represents a certain step forward, it also risks being interpreted as treating +4°C as an inevitable future, potentially downplaying the relevance of other climate scenarios.

The plan targets sectors such as buildings, urban planning, agriculture, and large corporations. However, key ministries—including the Ministry of the Interior, the Ministry of the Armed Forces, the Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs, and the Ministry of the Economy and Finance—are not involved. As a result, critical perspectives related to security, defense, diplomacy, and public finance are largely absent.

Moreover, the plan pays insufficient attention to small and medium-sized enterprises and sectors facing energy constraints, and it shows weak integration with mitigation policies. Adaptation requires not only technical responses but also the clear articulation of social and political priorities. The plan has been criticized for relying heavily on a liberal intellectual framework, with limited attention to social perspectives and decision-making processes. Another challenge is that the plan places strong emphasis on the need for further research, while failing to present the practical answers that are required immediately.

Against this backdrop, the ‘Paris at 50°C’ report, produced by the City of Paris, stands out for its concrete and intuitive presentation of the impacts of climate change on cities. Many members of parliament and local government officials regard it as an important foundation for future discussions. However, initiatives limited to Paris alone, and are unlikely to lead to nationwide legal reforms. It was therefore emphasised that diverse regions across France, including Lyon and other regional cities, as well as coastal and mountainous areas, must articulate their own needs and adaptation priorities.

Lyon, in particular, has attracted attention for convening a citizens’ assembly on adaptation, in which residents played an active role in deciding what should be protected. It is impossible to adapt perfectly to every scenario in every sector, and priorities must therefore be set within limited resources. In order to gain social legitimacy and acceptance for such choices, it is essential to enable citizens to participate directly in the decision-making process. In contrast, Paris has yet to implement mechanisms for building citizen consensus, leaving ‘Paris at 50°C’ largely in the conceptual stage.

Additionally, Mr Florentin has delivered lectures in cities such as Bordeaux, Strasbourg, Nantes, Dijon, Annecy and Marseille, focusing on how urban areas might experience extreme heat, and raising awareness of local climate risks and adaptation policies. However, many of these initiatives have remained one-off events and have not developed into sustained efforts.

Finally, Mr Florentin noted that his affiliation with the small Génération Écologie party, rather than one of the major Green parties, can make it difficult to establish formal political cooperation with other cities due to differences in political positions and factional dynamics. Although collaboration has progressed among citizens and municipal officials in other cities, it has not yet led to sustained cooperation between political parties.

[1] Mission d’information et d’évaluation du Conseil de Paris. Paris à 50 degrés : s’adapter aux vagues de chaleur.https://cdn.paris.fr/paris/2023/04/21/paris_a_50_c-le_rapport-Jc4H.pdf

[2] Most current air-conditioning systems are designed to operate properly only at temperatures below 43 degrees C.

[3] drieat.ile-de-france.developpement-durable.gouv.fr+6ecologie.gouv.fr+6climate-adapt.eea.europa.eu+6

Scenes from the Climate Academy

A wide variety of events and activities have been held in the Climate Academy.

A wide variety of events and activities have been held in the Climate Academy.

Rooftop Greening at the Climate Academy

Rooftop Greening at the Climate Academy

A room with house insulation models

A room with house insulation models

Models Demonstrating Rooftop Insulation Techniques

Models Demonstrating Rooftop Insulation Techniques

Explanatory Panels Displayed on the Academy Walls:

Explanatory Panels Displayed on the Academy Walls:

Left: A projected image of Paris in a future where rooftop greening has been widely implemented; Right: An illustration showing changes in building temperatures under scenarios with enhanced rooftop insulation and greening

Renovation of Charles Baudelaire Primary School

The street in front of the school has been closed to traffic and planted with trees.

The street in front of the school has been closed to traffic and planted with trees.

The roadway has been repaved in light-colored materials

The roadway has been repaved in light-colored materials

The street is closed to traffic and equipped with misting devices. When a button is pressed, a fine mist is released for a few seconds.

The street is closed to traffic and equipped with misting devices. When a button is pressed, a fine mist is released for a few seconds.

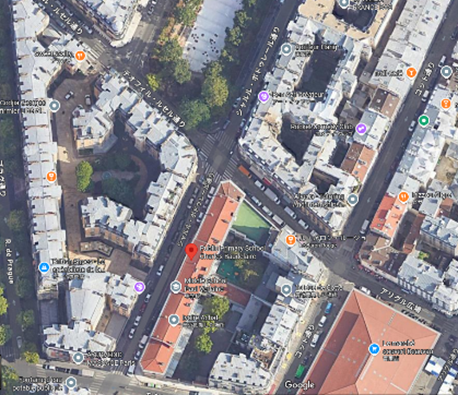

An aerial view of the primary school (Google image). The street in front of the school is now closed to traffic and has been planted with trees.

An aerial view of the primary school (Google image). The street in front of the school is now closed to traffic and has been planted with trees.

Leveraging a Climate-neutral Society

Leveraging a Climate-neutral Society